Science Cannot Prove That Things Don’t Exist

In general, biologists deal with actual objects. No matter how many rumors or sightings there are of yetis or Nessie, they are not the subject of biology. It is only when bits of hair or something are found in a yeti footprint that their analysis starts belonging to the category of biology.

A century ago, Inoue Enryo, who was famous as a scholar of yokai [supernatural beings in Japanese folklore], presented reasonable explanation of yokai phenomena based on the assumption that yokai do not actually exist. I, for my part, tried to describe the rokurokubi [a human-like monster with a very long neck] as an actual creature and analyze its biological mechanisms. It was a kind of thought experiment, perhaps delusional, or maybe an imaginative way to enjoy the “biology of yokai.” In either case, I had crossed the line as a biologist, of course.

Consciousness is another subject that is difficult to deal with scientifically. Questions at the level of whether consciousness exists medically speaking, or social awareness, can be the target of scientific studies, but when you step into the area of wondering why you exist at this moment, or why you are you and not someone else, objectivity is lost. When reflecting upon your own self, scientific logic no longer applies.

As for the consciousness of animals, some research has been done on monkeys, but it is by necessity limited to what can be observed objectively. Whether monkeys, or cats and dogs, have a human-like consciousness is something we can never really know, since we are not cats or dogs. Humans for that matter appear to act as if they are conscious, but when you probe deeper it becomes hard to tell whether they really are. For animals, including humans, biological logic ceases to apply. To take some extreme examples, earthworms or jellyfish, even plants may have consciousness. We can’t rule it out completely.

This is where we reach the limits of science. It is not just consciousness, science can’t prove that something doesn’t exist.

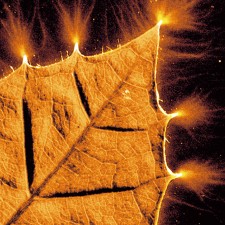

The Mimic Overkill of the Mimic Octopus

The mimic octopus is a recently discovered species, whose mimicry is on a completely different level than stick insects or leaf butterflies.

It takes on a wide variety of appearances, from sea snakes and lion fish to flounders and giant crabs. Nevertheless, its evolution can still basically be explained by Darwin’s theory of natural selection. That is to say, the octopus’s behavior is well adapted to its environment. A mimic octopus that can imitate a range of creatures has a selective advantage over an octopus that can only imitate a single other species.

That said, one would believe the octopus should be able to survive without going as far as this. The intelligence of octopi is quite developed, so perhaps in addition to biological instincts some function of its intelligence is at work. It is not unthinkable that it is doing it on purpose.

The great apes too play or do things that seem unnecessary from a human point of view, but in the case of the mimic octopus we know almost nothing about its ecology, so it is too early to tell.

Column 1

Mimic OctopusThaumoctopus mimicus, an around 60 cm long species of octopus that was first discovered in 1998 and that inhabits the coasts of Indonesia and tropical seas in Southeast Asia. Apart from sea snakes and lionfish, it has hitherto been observed to mimic at least 15 different other types of creatures, including jellyfish, starfish and rays.

The Danger of Personification and the Allowance for Variation

In any case, it is dangerous to assign meanings to animal morphology and behavior based on human standards. For example, certain species of shrimps live in symbiosis with gobies. The goby protects the shrimp from enemies, and the shrimp provides housing for the goby. They lean on each other, you might say. It is an explanation that is easy to understand, but in actual fact no such human emotions are involved at all, indeed no emotions whatsoever. The relationship is just the result of cold biological laws.

However, claiming that the morphology and ecology of all living creatures is the result of adaptation would not be true either. For example, the horns of treehoppers are extremely varied, and include some that look utterly bizarre to a human observer. They hardly have to be that strange for adaptation. It is difficult to believe that those shapes led to increased chances of survival.

According to molecular biology, initially random DNA suddenly mutates, there is a combination of various environmental factors, and the species that can adapt survive. Even if the mutations are somewhat excessive, as long as they are within the margins of the adaptable range, a broad diversity can appear, even if they look strange to humans, like the treehoppers. It could be that the mimic octopus has the margins and allowance to let that happen as well.

Diversity Was Born out of Death

What biological death means is also a hard question. Usually when we talk about death, we refer to the death of individuals, but reproductive cells go on living. They have remained alive for 4 billion years. The death of individuals was born with the division of labor between reproductive cells and somatic cells. It is advantageous for the life form to let all the many mutations that have accumulated in the somatic cells be reset, or in other words die, and start over with a fresh new body. For life to acquire diversity was inseparable from acquiring death.

Every time a somatic cell divides, the mutations pile up in the genes. In the case of humans, cancer cells are clearly abnormal, and it can be seen how mutations have accumulated by comparing them to normal cells. However, there is no standard to compare normal cells to. If you compare them with other normal cells, you cannot tell how much each of them has mutated. A meaningful comparison would be with the genetic information in the fertilized egg that later became that person, but that is impossible to investigate.

Column 2

HeLa CellsHeLa is a cell line of human origin that is widely used for tests and research. The immortalized cells derive from the tumor of a woman in her 30s, who died from cervical cancer in 1951. It is believed that some of the genes of the virus that infected epithelial cells of the cervix, causing the cancer, have been integrated into the chromosomes of the cell and were involved in its malignant transformation and immortalization.

Reproductive cells may also change, of course. The cell divides many times, and each time the DNA is replicated which means that some changes will occur. However, the repair function of reproductive cells is much better developed than for somatic cells, so the risk that the genetic information will change is low. It’s not zero, though. In other words, the genetic information in your reproductive cells and your somatic cells is quite different. The genetic information that you pass on to your children is quite different from that of your current somatic cells.

Can the Program of Death Be Rewritten?

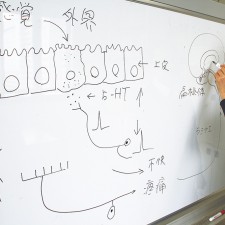

The reason that HeLa cells are immortal, or appear to be immortal, is that they express an enzyme called telomerase, that preserve the telomeres. There is no doubt that death is programmed via the telomeres. Since somatic cells express virtually no telomerase, the telomeres grow shorter for every cell division, until eventually the chromosome structure cannot be maintained and the cell can no longer divide. That is one of the causes of aging. There are other causes as well, apart from the telomeres, but by manipulating the telomerase it might be possible to extend the length of life or remain youthful for longer.

Whether it is as simple as just expressing telomerase is something that needs to be verified, of course. For that purpose, it is necessary to make all the cells express telomerase, which entails some sort of operation at the stage of the fertilized egg. Now, creating such a telomerase-expressing baby is probably ethically impossible, but if we could explain the mechanisms of telomerase expression, we might be able to develop drugs.

Recently, something like genes for longevity have been discovered, but unfortunately there is a tendency among people as soon as anything is found to believe that it will solve everything. Organisms are not that simple.

Column 3

TelomeresTelomeres are located on the distal end of eukaryotic chromosomes to protect the ends of the chromosomes. Since telomeres are shorter in aged cells, the length of the telomeres is believed to limit the number of cell divisions. Furthermore, elongation of telomeres is done by means of an enzyme called telomerase, and for cells that lack this enzyme, the telomeres grow shorter with each cell division. Human somatic cells do not express telomerase, or only very weakly.

If iPS cells are separated in infancy, they might be applied to various things, and when that person is in their 70s or 80s, it might be possible to cure their diseases by changing their cells into iPS cells. But iPS cells should absolutely not be used to make children, or things like that, since the mutations will accumulate. Nobody is doing that kind of research, and the research technology doesn’t even exist. It is a serious problem that this fact is not better known. Rushing to create practical applications before the basic research has been done is especially dangerous for topics that concern life itself.