Mites as Decomposers

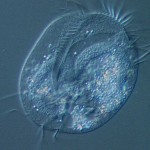

There are thought to be about 1850 species of ticks and mites in Japan, and some 50,000 in the world. Many people put on a frown just by hearing the very word, but in fact out of all the species in the tick and mite family (Acari) only about a tenth are harmful to man. For example, the oribatid mites that I am studying are totally harmless to humans and other animals, and live quietly under fallen leaves and decaying trees in the forest. But when you take a closer look, you’ll find that mites play a very important role in the ecosystem as “decomposers.”

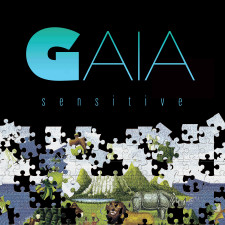

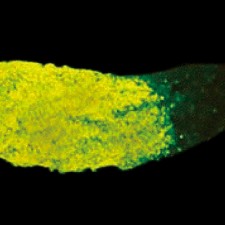

Indotritia javensis. The black spots inside its body are “leaf burgers.”

Mites eat plant residues like fallen leaves and dead branches, breaking them down finely, and then deposing the result as droppings (what I sometimes call “leaf burgers”). These droppings are then further broken down by microbes into inorganic substances, which in turn are absorbed as nutrients by the roots of plants. If the mites were to disappear, this whole recycling system would grind to a halt. In this indirect way, mites are actually even quite beneficial to humans. An interesting thing is that the mites are specialized into “fallen leaf handlers,” “dead branch handlers,” etc., just like the way trash put out by humans is sorted into “combustible waste” and “incombustible waste” and then collected by different recycling companies. The fact that so many mite species function as decomposers is essential to the maintenance of the ecosystem.

Before They Vanish Unseen

The number of species on our planet is said to be around 1.4 million, but some scientists estimate that if we were to count and give names to all the nematodes that dwell in the mud at the bottom of the oceans, there might be as many as 200 million. That is to say, most species do not even have a name yet.

But however numerous the species may be, they are now becoming extinct at a rapid pace. Plenty of species have disappeared since the ancient past as well, of course, like the dinosaurs, but most did so little by little over periods of several million years. This time, however, the mass extinction is taking place over an extremely short span of a mere 50 – 100 years. That abnormal state is due to the activities of man.

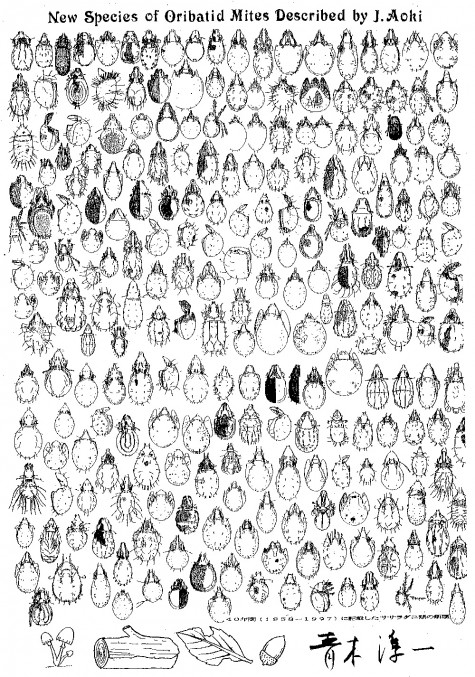

In Japan, people mourn the vanishing of the crested ibis, but I doubt that many would fell a tear if a kind of mite were to disappear from the surface of the Earth. That is why I keep searching for new mite species and giving names to them as evidence that such creatures have existed on our planet. So far, I have surveyed 2900 places all over Japan and discovered and documented about 300 new species.

Sketch of mites by Prof. Aoki

Mites as Indicator Species

One thing I noticed during my surveys was how the breadth of adaptation varies between different species. While some mites are found in any kind of place, others only live in virgin forests or groves of mixed trees. On the other hand, there are also mites that thrive in man-made environments like plantations or golf courses. I thought this was interesting and got the idea of using mites as “indicator species.” An indicator species is an organism that is used to measure the condition of its particular environment. For example, water-dwelling bugs are used to measure pollution in rivers. In a similar way, I decided to utilize mites to examine the richness of soil.

First, I selected 100 representative species, based on my research thus far. I then divided them into five groups, A to E, from those that are highly susceptible to environmental changes to those that are unflustered even under harsh conditions. I further assigned a number of points to each group: 5 points for mites in group A, 4 for group B, etc., so that even if just a single mite of a certain species is found during the investigation of the soil, the corresponding number of points are added. In this way, I was able to compute an environmental index.

Let me remind you here that the number of individuals is not important. The score doesn’t change even if a hundred mites of the same species are found. The way it works is that the more “high score” species that are found, the higher the evaluation (average score). Even if there are lots of mites but they are only of the “low score” varieties, that couldn’t really be called a good environment.

The reason that mites are excellent as indicator species is that the same species are always found in the same environments. With bodies small enough to be blown away by the wind, they disperse and migrate so easily that they soon live absolutely anywhere they possibly can, and are completely absent in places where they can’t live. There are not even places where they don’t happen to live due to some topographical feature or the like. The seasons don’t matter for the result, nor do night and day. They are indeed ideal indicator species, except perhaps for the fact that it is very hard to tell different mite species apart.

Before, I was sometimes asked ”what on earth is the point of naming mites?” but when I discovered this application I was able to show that my long years of research had not been futile.

A kind of Neoribates, discovered in the Kerama Islands, Okinawa.

Our Planetary Life Support System

As I said before, when using mites as indicator species for an investigation, the important thing is not the number of individual mites but the number of different species. In other words, the fact that many different biological species inhabit an environment is evidence of the richness of that environment. This line of thought is of course related to the idea of biodiversity that has become so important in recent years.

When you compare planted forests of, say, cedars or cypresses with virgin forests, you find that the latter are far more resistant to hurricanes and other calamities. They are full of a variety of living things that sometimes get along just fine, sometimes snarl a bit at each other, but somehow manage to keep that fine balance that makes for an abundant environment.

“Who cares if mites would disappear,” some people may think, but mites too play an important part in the maintenance of the Earth’s ecosystem. If they were to vanish, life on our planet would grow weaker. As somebody said, “biodiversity is the life support system for all living things on Earth.”