From training water rescue dogs to underwater search dogs

I’ve always loved dogs and kept a number of them as pets. Ever since then I’ve found dogs’ sensory abilities amazing, and gradually I began thinking that “what if we could bring out the potential capacities of dogs and strengthen them to train dogs for various socially useful functions, just like police dogs or drug detection dogs?” About 25 years ago, I quit my old job and moved to Tateyama in Chiba prefecture. That’s when I started working with dogs in earnest.

My first project was to train a “water rescue dog.” These are dogs that jump into the water and swim out with a rope or a life preserver to people who are about to drown at beaches and places like that. Once when I was training a dog on the shore, by chance an angler happened to fall into the sea, and both the dog and I immediately rushed to the rescue.

However, many victims of accidents at sea sink to the bottom without floating up again. In case of drowning, decomposition gases inside the dead body causes the body to float up to the surface, but as soon as those gases have evaporated it sinks back to the bottom. With the feelings of the bereaved families in mind, I started to think “if at least the body could be found,” and had the idea that the smell of the evaporating gases from the corpse ought to provide a way of detection.

“There’s no way to detect smells under water,” people told me, but I was convinced that dogs with their superior sense of smell could do it. My policy has always been that “there’s nothing you can’t do. There should be some way to do it, you’ve just got to find out how.”

Then I trained a black Labrador retriever named Marine, who has an incredible sense of smell, and after about six months she was able to discover a dead body at a depth of 20 meters. She was the world’s first underwater search dog.

Do diseases have characteristic odors?

When you let a police dog sniff an object belonging to a criminal, the dog soon starts tracking that smell. How can it do that? Well, everybody has their own smell and that personal smell gets transferred to the clothes and shoes we wear, and dogs can recognize it. Smells that humans could never tell apart are no problem for dogs to differentiate.

Once I tried the following experiment. I breathed into a plastic bag, tied it up and hid it among the rocks. The dog soon found it. Next, I hid a cucumber among the rocks and ate another cucumber myself. Immediately afterwards I brushed my teeth so that the smell of cucumber wouldn’t linger in my mouth. After 20 minutes, when digestion had begun in my stomach, I let the dog sniff my breath and then search for the cucumber hidden among the rocks. She found it without a problem. Apparently she was able to pick out the cucumber scent even from that complex mix of different odors.

This led me to wonder whether diseases also have their own characteristic smells. You can regard a disease as different phenomena occurring inside the body than in a healthy body. What if the internal condition that causes a disease had a peculiar odor? Perhaps it might be possible for a dog with its acute sense of smell to determine whether a person was afflicted with that disease or not, I thought.

Training cancer detection dogs

From training water rescue dogs and underwater search dogs I was confident in dogs’ excellent olfactory abilities, and was fascinated by the idea of discovering diseases by their scent. When I considered which disease to target, the answer had to be the top killer: cancer.

To proceed with my research I needed to let the dog learn the characteristic odor of cancer, and for this purpose I needed to get hold of breath or urine samples from cancer patients. I contacted over a hundred hospitals but all of them turned me down. Maybe that was only to be expected; the hospitals’ ethics committees would hardly give permission, and above all there was the issue of the patients’ personal information. But even before that, many hospitals simply refused to listen to me. “If we could diagnose diseases by their smell, we wouldn’t need any doctors, would we?” they said. Back then (this was around 2004), nobody had the imagination to link diseases with smell.

Just when I was about to give up, a friend introduced me to the director of a certain hospital. Far from denying what I was thinking, on the contrary he said that “when people with cancer come to the clinic, I can smell it.” That encounter was my breakthrough, and I was able to obtain breath samples from patients with esophageal cancer, lung cancer and stomach cancer.

The dog I chose to train for cancer detection was Marine, who had already displayed her extremely acute sense of smell as a water search dog. After only about one week she was able to distinguish breath samples from cancer patients. Marine’s nose is amazing, even compared to other dogs, and if I hadn’t met her, I believe I never would have started researching cancer detection dogs.

Around that time, I was interviewed concerning water search dogs by a magazine for dog lovers, but when I told them I was training cancer detection dogs too, that became the theme of the article. A newspaper journalist who had read that piece came to visit and wrote an article with the heading “Cancer detection dog sniffs the Nobel Prize.” It became big news, and suddenly hospitals from all over the country started contacting me.

Experiment setup for dog cancer detection. After the dog has memorized the smell of the breath of cancer patients, one pack containing a breath sample from a cancer patient and four breath samples from healthy people are put in the boxes. When the dog discovers the breath of the patient, it is trained to sit by that box.

Announcing the success of cancer detection dogs to the world

The first medical professional who collaborated with me in full-scale joint research was Dr. Hideto Sonoda at Kyushu University (now at Imari Arita Kyoritsu Hospital). Dr. Sonoda advised me that “we must turn it into genuine science, rather than something people find unscientific” and he helped me improve my experiment method:

A group of five boxes are put in a room. In four of those five boxes, I put medical breath packs containing the breath of healthy people, and in one box I put a pack with the breath of a cancer patient. Then I let Marine discover which one is the patient. This experiment requires a high level of concentration on behalf of the dog as well, and it is difficult to continue for very long.

In 100 trials over a period of one year, she was able to determine the breath of the cancer patient with an accuracy of 98%. Dr. Sonoda and I compiled our results in a paper that was published in the world-famous medical journal Gut in January 2011. Now hospitals from all over the world started calling me. This was the moment when our research was indisputably recognized as science.

Later I learnt that research on cancer detection dogs had also been performed in the United States and Great Britain, but their results had not been particularly good. However, after our paper was published, similar research is now conducted in over a dozen countries around the globe. You could say that Marine’s miraculous sense of smell changed the course of the world.

I have also done joint research with Dr. Masao Miyashita at Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital, where Marine was able to sniff out breast cancer, uterine cancer and other gynecological cancers with almost 100% accuracy. These results were presented at a medical convention here in Japan.

Identifying cancer markers toward the development of analyzers

Cancer dogs can distinguish the breath of cancer patients from the breath of healthy patients. So what then are those odorous substances that the dogs can detect? That is what we are currently researching.

People often misunderstand this, but my goal is not to train a large number of cancer dogs. If we could identify what it is that give cancer patients their characteristic odor – most likely something that derives from cancer cells – we should be able to develop a device to detect that substance, a sensor. And if that sensor was then widely distributed, early cancer detection would become much easier. Simply by blowing into a device you would know if you had cancer or not, instead of having to use X-rays or blood tests.

The reason cancer is so feared is because it is a deadly disease, but the chance of recovery increases with early detection. The problem with early detection, however, is that no valid marker has yet been discovered to determine whether somebody has cancer or not. Enormous amounts of money is invested in cancer marker research all over the world, and if a valid marker could be found, the discoverer will surely get a Nobel Prize. What cancer dogs have shown us is that smell could be such a marker.

But even if an analyzer that can detect cancer from your breath was developed for practical use in the near future, and introduced at medical institutions nationwide, if people don’t examined, because they can’t be bothered or because they hate doctors, their cancers won’t get detected at an early stage. Then what do you do?

Once a device has been constructed, it will gradually be miniaturized. If you could make it as small as a computer chip, one idea would be to put it into smartphones so that it could instantly analyze your breath when you’re talking on your phone. It might sound like a pipe dream, but people used to tell me that “no way could you detect cancer by smell.” But thanks to Marine, I’ve already come this far.

The dogs lead the way

At the moment we have five cancer dogs at our kennel. Once of them is a clone of Marine created at Seoul University in South Korea. That dog also has a superior sense of smell in the same league as Marine and promises to lead our research in the right direction. I receive many requests from abroad to teach them how to train cancer dogs. Sometimes I go there to instruct them, and sometimes the trainers come here to Japan, but I hear the results haven’t been that good. I was really lucky to come across Marine from the very beginning.

Our research is now one step from identifying a substance for lung cancer. However, to specify that substance beyond doubt will still require a lot of time and funds. Say that substance A is a potential marker for lung cancer. You then need to carefully investigate whether A isn’t also present in the smell of other cancers or the smell of healthy people as well.

For this purpose too we rely on the olfactory abilities of cancer dogs. While we are trying to determine cancer markers, I feel the dogs are trying to show us “here, it’s this one!” With the courage to try new things and a bit of imagination, people can do anything. God only gives us challenges that we can solve, I believe.

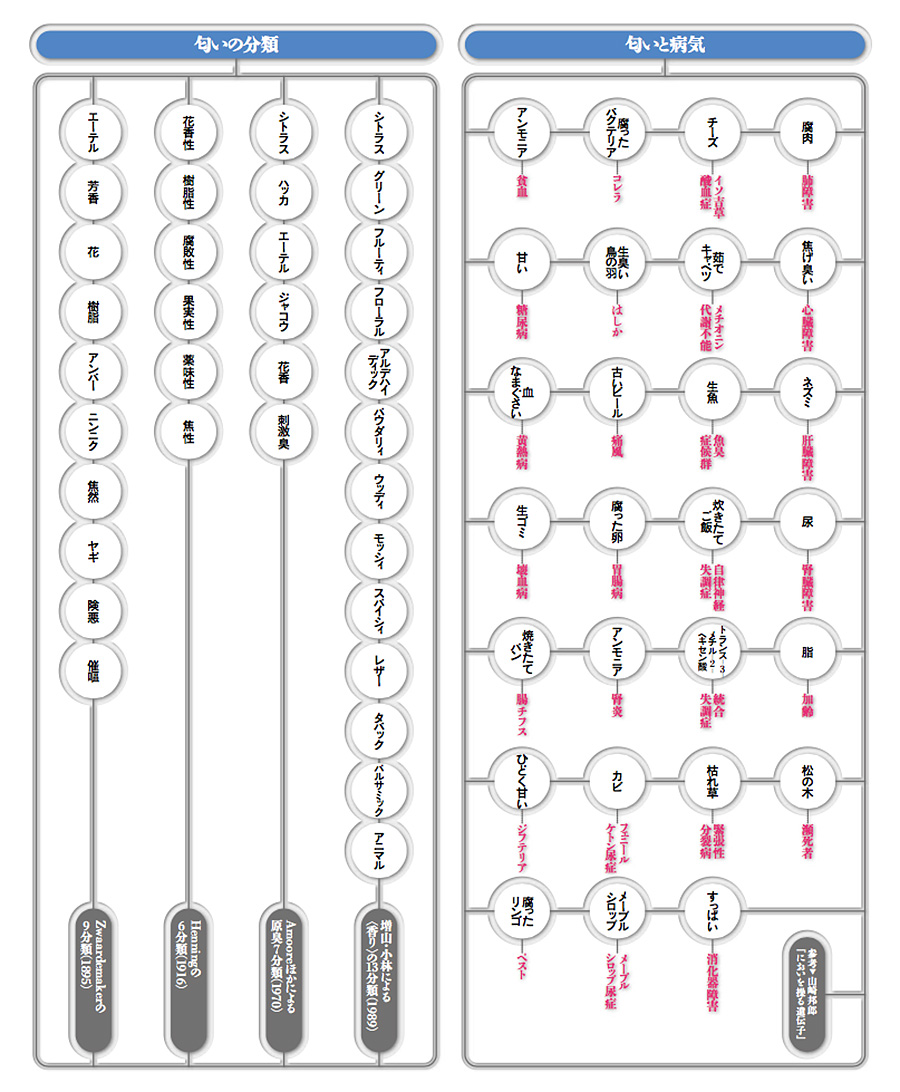

Diagram 3

Classification of Smells / Smells and Diseases

There are around 100,000 discernible smells, and the human nose is believed to have receptors for over 300 types. Many different classification schemes have been devised over the years, but there are still no firm definitions.

Relationships between particular smells and various diseases have also been noted since ancient times, and some of them are utilized in general medicine.