From a fascination with the stars to the opening of the Yatsugatake observatory

When I was a kid, I loved science and imagined myself in the future wearing a white coat and working in a laboratory. At the same time, pollution was becoming a big social problem and I started to think that “science might ruin our planet some day.” I admired the entomologist Fabre’s stance of observing nature as it is, and eventually my interest turned to the stars.

In junior high school, I joined the science club, and on a field trip to a planetarium I was so impressed that I bought a guide book to the constellations on the way home. Every night my friends and I used to watch the stars, but a real telescope was far beyond our reach.

In a book I read an article about “how to build your own reflecting telescope,” and spent my whole summer vacation building one when I was 13. I couldn’t wait for it to get dark, and could hardly even get my dinner down. When I finally looked through that telescope from our back yard and suddenly could see all those truly beautiful stars I was so excited that I jumped with joy. That’s my roots, I’d say.

I then got interested in observing variable stars and meteors. These are profound areas that I got completely absorbed in. I used to think when I was looking through my telescope that “maybe I’m the only one on earth who is observing this star right now.”

I wanted to share my excitement at watching the birth and death of stars, distant galaxies and the shape of the universe, and let other people see it with their own eyes through a large telescope. If there isn’t any such place, I’ll have to build one myself then, I thought, and opened the Yatsugatake South Base Observatory in 1985. The reason I selected Yatsugatake was that the Pacific coast climate has many clear days, the location is more than 1,000 meters above sea level and relatively free from human-caused particle dust that obstructs observations, and it is also easily accessible thanks to a train station nearby.

Falling meteors and plasma tubes – meteor observations on the FM band

The observatory was open to the general public and I lived my life with day and night reversed, giving explanations all through the night while continuing with my own observations of asteroids and comets. I’m the co-discoverer of 55 asteroids and two comets (147P/Kushida-Muramatsu and the periodic comet 144P/Kushida).

In the summer of 1993, the Perseid meteor shower was expected to be huge around August 12, and I was thinking about how to observe it. If the weather was fine, no problem, but if it was cloudy you couldn’t even see the meteors. At the very least, I wanted to know their count, so I decided to observe them using FM radio waves.

AM radio utilizes long wavelengths on the HF band which are broadcast by the station and reflected by the ionosphere around 100 km above the earth’s surface. They are then further reflected by the ground so that they travel very far. The short wavelengths of FM radio waves (on the VHF band), on the other hand, are not reflected by the ionosphere but travel right through. That is why you can hear AM stations from far away, but only listen to FM radio close to the station. However, when meteors fall through the atmosphere and collide with oxygen and nitrogen molecules, they cause a plasma state (plasma tubes) to form in the vicinity of the ionosphere. These plasma tubes reflect the FM radio waves that would normally pass through the ionosphere, so that you briefly can receive distant FM stations. Back when I was in junior high school, I used to turn my FM radio to stations I usually couldn’t receive in Northeastern Japan or Hokkaido and listen all night long through my headphones. Mostly it was only white noise, but sometimes you could hear music or the DJ’s voice for a few seconds, and then I knew that a meteor just fell!

Strange patterns on the chart recorder a few days before an earthquake

I decided to try this observation method for the 1993 Perseid meteor shower. However, I couldn’t bring myself to keep listening to white noise anymore, so instead I attached a chart recorder to an FM tuner.

On the night in mid-August when the Perseids where scheduled to appear, the chart recorder started drawing beautiful, straight lines. Occasionally there was a spike in the line. This was evidence that the tuner had received FM radio waves reflected by a plasma tube due to a falling meteor, a so-called meteor echo. In just half an hour I was able to confirm 10 meteors.

After a while, however, the recorder started drawing a strange, fat baseline that I’d never seen before. What on earth is this, I thought, but after about 30 minutes the baseline went back to normal. I had read several books on radio observations of meteors, but none of them mentioned such a phenomenon. It remained mysterious but I kept on with the meteor observations. Then three days later I heard on the news that Okushiri Island off Hokkaido had been hit by a strong earthquake and suffered major damage.

At that moment I instinctively felt that that fat baseline had something to do with the earthquake. The tuner I used for the meteor observations had been set to capture radio waves from an FM station in Tohoku, and the earthquake had occurred on Okushiri Island in the same northerly direction… I shook my head, but from then on I checked the chart recorder carefully whether that fat baseline ever reappeared.

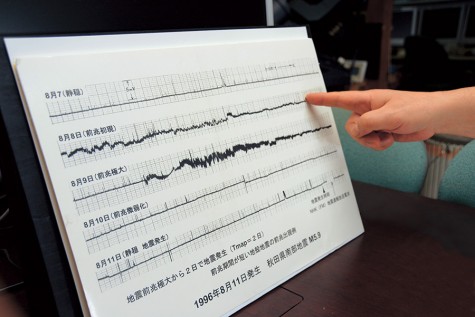

A bit later, another strange line appeared, not a fat one this time, but an undulating baseline. At first the undulation was weak but it grew stronger over the next few days, and then disappeared again. And once again, the news reported another earthquake a couple of days later. The undulating line too seemed to be earthquake-related.

As long as the normal, straight baseline continues, there won’t be any earthquake, but when a thick baseline or an undulating baseline appears on the chart recorder and then stops, an earthquake will occur two or three days later. But when I told my friends about this phenomenon they just laughed at me and thought I was joking.

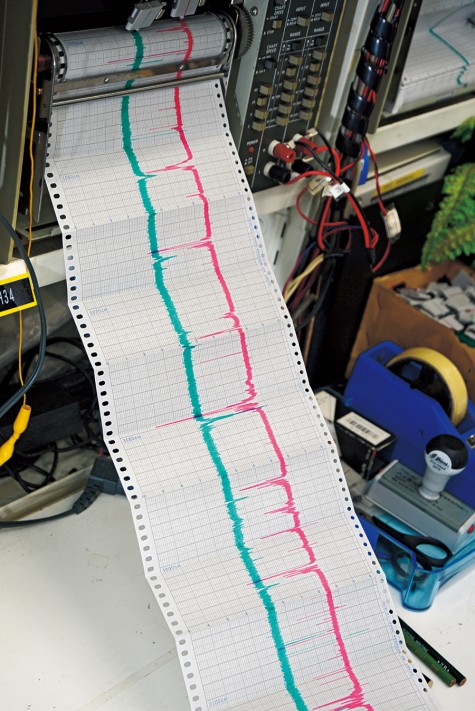

Chart recorder paper. Sudden spikes are evidence of reception of FM radio waves reflected from meteor plasma tubes or aircraft.

Seismologists deny everything, but Kushida sticks to his FM radio wave observations

On January 14, 1995, the chart recorder started to draw another unusually fat baseline. This continued on the 15th and 16th. Then in the morning on the 17th my dog was howling like crazy. I had a very bad feeling and turned on the TV, and all the news was about the huge earthquake that had struck in the Kansai region (the Kobe earthquake). When I hurriedly checked the recording paper, the fat baseline had already stopped.

I compared my accumulated observation data with data about the earthquakes that had occurred during that period, and was convinced that the FM radio wave observations had captured advance signs of earthquakes, so I steeled myself and gave a press conference at the Yamanashi Prefecture Government’s press club.

“I am presenting my data so far, and would like experts in seismology and geophysics help me do a full-scale investigation,” I appealed, but the reception was frosty. When the journalists who had attended the press conference asked seismologists their opinions, they just denied everything and said it was impossible. They wouldn’t trust somebody who wasn’t a university professor or belonged to a public observatory, but just a guy with a private observatory.

What upset me the most was the attitude of those seismologists, who simply rejected my results out of hand, without bothering to verify my data or my observation methods. That is something a real scientist must never do, I thought.

To withdraw at that point would have been too frustrating, so instead I decided to increase my observation equipment and continue with my FM radio wave observations.

The observatory closes and public earthquake prediction experiments start instead

In May 1995, I captured another anomaly that seemed to be the sign of an earthquake. The line was even thicker than for the Kobe earthquake, and the direction was North. Perhaps Hokkaido? I phoned NHK and the local newspapers, and told them a major earthquake was likely to occur in the Hokkaido region within the next couple of days. I was desperate, but as usual they didn’t really want to listen.

But the earthquake did in fact occur. Only it wasn’t in Hokkaido, but further North in Sakhalin.

No matter how the experts denied my work, I was convinced that what I was doing was correct, and made up my mind to continue with these observations for a long time and thoroughly investigate the relationship between precursory phenomena and earthquakes.

I emptied my savings account and borrowed money from my father to further enhance the observation equipment. I also bought a large number of chart recorders. Then I noticed that the computer that was driving the telescope in the observatory was affecting the radio wave observations. This was a serious problem. If I couldn’t use the telescope, I could no longer keep the observatory open for business. But if I couldn’t keep the observatory open and continue with my observations at the same time, I decided to close the observatory temporarily and focus on the observations. Unfortunately this also meant that I lost my source of revenue, and after much thought I launched a project of “public experiments in earthquake precursor detection.”

The idea was that I would send earthquake precursor data and analytical information by fax to those who agreed to take part in return for an experiment participation fee. If you can know in advance when, where and how strong an earthquake will occur, you’ll have time to make preparations for it.

The experiments were scheduled to start on August 1, 1995, but already on July 26 I observed signs of an earthquake, so I sent out my first fax on the 28th saying an earthquake with a magnitude of 5.0±0.5 was likely to occur in the Kanto area on July 31, ± 2 days. Then on the 30th an earthquake did occur in northern Chiba prefecture with a magnitude of 5.3.

In the beginning I believed I would be able to obtain clear results if I continued for a year or so, but here I am still going strong after 20 years. The number of participants in the public experiments is about 400, including companies, and they keep supporting my work.

During all these years, the observations have continued 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, without a single day off. The recording papers of the 40 chart recorders have all been saved.

The undulating baseline recorded here was a precursor of an earthquake in southern Akita prefecture (August 11, 1996).

Toward real earthquake forecasting

The earthquake forecasts are not just one steady row of hits; there have been quite a few misses as well. For example, before the Tohoku earthquake on March 11, 2011, I was observing a precursor since the 8th but couldn’t distinguish it from another long-running precursor that I was observing at the time, so I was unable to send out any advance information. I still regret that.

However, for each mistake, I look at the data anew and make new discoveries, and over the years I have accumulated a wealth of empirical data concerning the relationship between precursors and actual earthquakes. Thanks to this, I am now able to predict, with a certain margin of error, the epicenter, magnitude and date of earthquakes.

I have learnt that in some cases the precursor period is a mere three days, like for the Kobe earthquake, while in other cases it may go on for three and a half years, such as for the Iwate-Miyagi inland earthquake in June 2008. “Long-term precursor no. 1778,” which I’ve been observing since 2008, indicates the possibility of a strong earthquake in the Kinki region (or possibly the Tohoku region) at the end of July, 2015. I’m in the midst of investigating this.

I don’t like the term “earthquake prediction,” and prefer calling it “earthquake forecasting.” In the case of the weather, it’s called a weather forecast; it’s not called a weather prediction, is it? Earthquake forecasts aren’t some sort “prophecies” revealed by the gods, it’s a scientific attempt to predict earthquakes based on an analysis of clear indications. If the weather report says that “it’s likely to rain today,” you bring your umbrella. You don’t panic when it suddenly starts raining. In the same way, if you know in advance when an earthquake is going to strike, you can make preparations for it and reduce the damage.

I hope that such a time will come, and in the meanwhile I keep observing.

diagram 2

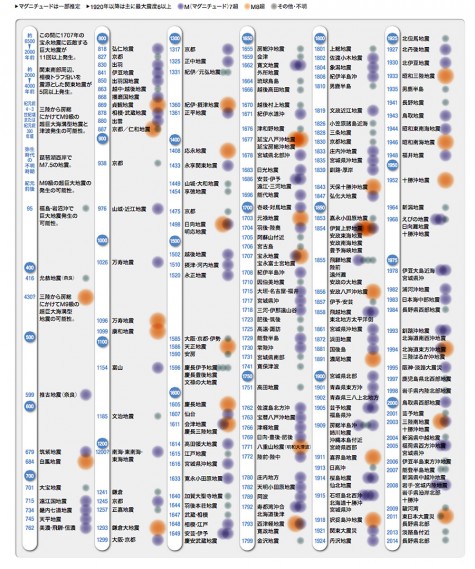

Japan – The Earthquake Archipelago

The history of Japan is also a history of earthquakes. The further back in time you go, the fewer records there are, of course, but an M6 class earthquake seems to occur almost every year somewhere in Japan or its vicinity.

Below is a list of earthquakes with a magnitude of 6.5 or greater that have had a major effect on the lives of Japanese people.